experience with mpMRI and targeted biopsies to precisely

identify APCs originating from the TZ.

Our group

[4]and others

[5,15,16]have published

precise morphometric and anatomic descriptions that led

us to explore this concept of APP in very carefully selected

patients after detailed informed consent.

In each of our cases, the TZ-originated cancer invaded, or

was entirely confined, to the AFMS. As such, simple

prostatectomy (BPH enucleation) would have been insuffi-

cient because it would not have excised the AFMS. We

learned that prostate volume (should be

>

42 cm

3

, which is

the 25th percentile of whole-gland volume of the no-

recurrence group) (Supplementary Fig. 2) is an important

factor for the success of the procedure. The technical

challenge of partial prostatectomy is not at the apex or at

the anterolateral aspect of the gland where the dissection

planes are similar to RP; the challenge is to ensure negative

margins posterolaterally at the PZ site. One patient (case 10)

with GS 7 (4 + 3) was included and was one of the four

patients who recurred. This inclusion criteria of the GS score

7 (4 + 3) or higher should be considered oncologically

incorrect. This case had a detectable PSA at 3 mo after RP

completion. Therefore selection criteria in the four men

who recurred were not so strict, and their results help refine

the selection criteria of patients as candidates for the

technique in future studies. Additional criteria for selection

should include whole-gland volume

>

40–45 cm

3

. The

technique may also include frozen section assessment of

the PZ margin.

Focal ablative therapy is a suboptimal treatment option

for PCa located in the anterior apex of the prostate because

of potential thermal diffusion injury to the external striated

sphincter, neurovascular bundles, and/or urethra, as well as

interference from the pubic symphysis. To the best of our

knowledge, the outcomes of focal high-intensity focal

ultrasound, cryotherapy, or laser ablation focusing on this

specific location are not available

[17] .We are acutely

aware that this concept of surgical focal excision is

controversial. This concept is open to the valid critiques

levied at focal ablation for PCa, such as uncertainty

regarding the natural history of untreated cancer foci,

uncertain post-treatment monitoring using PSA and MRI,

lack of long-term oncologic outcomes data in a larger

cohort, and lack of QOL data compared with traditional

treatment strategies

[18,19]. However, given that the

cancer lesion is surgically excised, it can be subjected to

accurate pathologic staging/grading, an aspect that is not

feasible with ablative partial/focal therapy

[20]. As for any

focal treatment, the remainder of the gland should be

devoid of any known foci of significant PCa, and it should be

possible to perform a completion of radical procedure in

case of recurrence or de novo cancer during follow-up.

However, a strength of our study is the meticulous reporting

of all relevant data regarding PSA, MRI, histopathology,

follow-up continence and potency questionnaires, and our

data with 30 mo of follow-up (range: 25–70).

This initial experience with robot-assisted APP provides

the following insights. First, the technique is feasible and

safe. Partial prostatectomy was not judged to be more

difficult than RP by the participating surgeons, all of whom

had expertise in robot-assisted surgery. Second, functional

outcomes were satisfactory. No patient reported stress

incontinence, in contrast to a 16% incontinence rate

following robot-assisted RP

[21]. Erectile function was

maintained at 6 mo in 10 of 12 men (83%) who were potent

preoperatively, which compares favorably with the 12-mo

potency rates of 54–90% after RP

[21]. Going forward, QOL

questionnaires should be added to assess overall benefits or

harms. Third, median PSA was 0.4 ng/ml (IQR: 0.3–0.7) at

3 mo. This value is close to the value of 0.6 ng/ml (range:

0–1.3) after a simple robot-assisted RP

[22], but lower,

probably because some of the PZ and most of the anterior

and apical prostate were resected. There is currently no

accepted definition for biochemical disease recurrence after

focal therapy

[23].

Fourth, our 29% anterior location rate of positive margins

(PMs) should be compared with RP anterior location rates,

in which the PZ was not preserved. However, our series is

made of highly selected cases that do not reflect the whole

spectrum of APC. Hence positive margin rates of 22%

anteriorly and 37% at the BN locations were observed in a

series of 55 RPs with TZ-originated cancer

[24]. A 46% rate of

PMs was observed in a series of 68 patients for which APC

[(Fig._6)TD$FIG]

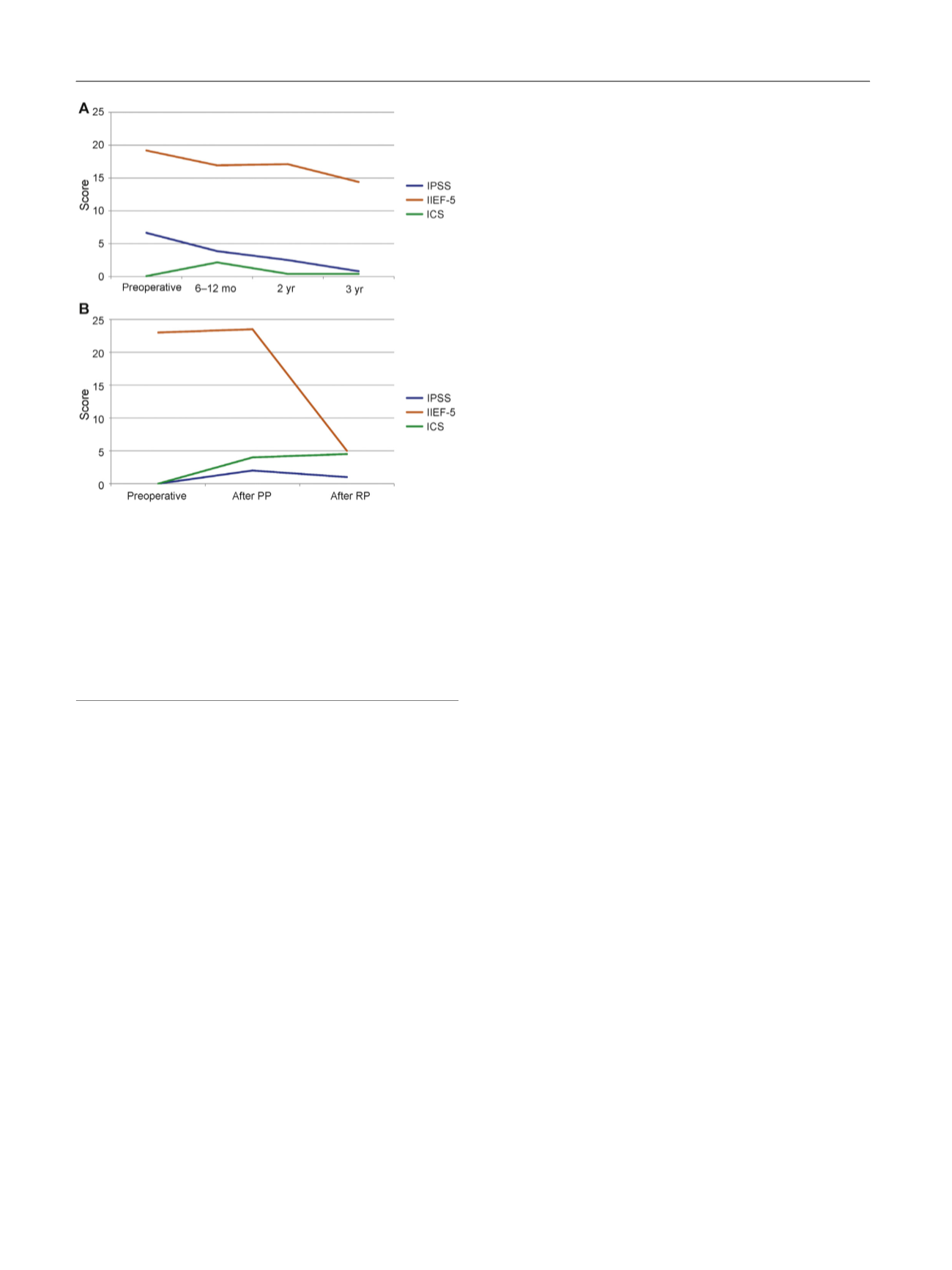

Fig. 6 – (a) Median International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS),

International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF)-5, and International

Continence Society (ICS) scores from baseline to 3 yr. ICS score

remained almost unchanged with no incontinence. There is gradual

improvement of the median IPSS score and a gradual decrease of the

median IIEF-5 scores. (b) Median IPSS, IIEF-5, and ICS scores from

baseline to after anterior partial prostatectomy and to after complete

radical prostatectomy for the 4 of 17 patients who had cancer

recurrence diagnosed at months 2, 24, 25, and 30.

ICS = International Continence Society score; IIEF = International Index

of Erectile Function; IPSS = International Prostate Symptom Score;

PP = partial prostatectomy; RP = radical prostatectomy.

E U R O P E A N U R O L O G Y 7 2 ( 2 0 1 7 ) 3 3 3 – 3 4 2

340