variables in the multivariable Cox regression analysis. The

progression score contained independent prognostic infor-

mation when compared to clinical risk factors and EORTC

risk scores

( Table 2 ). A nomogram for progression-free

survival (PFS) based on continuous EORTC risk and

progression scores is shown in

Fig. 3, together with an

associated calibration plot and receiver operating character-

istic (ROC) analysis for predicting 2-yr PFS. Combining the

progression and EORTC risk scores significantly increased

the predictive accuracy from 0.78 to 0.82 (

p

<

0.001). The

calibration plot shows substantial uncertainty for high

probabilities of progression, and the ROC analysis shows

that the combined score has better specificity at lower

sensitivities compared to the EORTC score, but is otherwise

very similar to clinical information alone.

In addition, we found that the progression score was

associated with previously identified classes in NMIBC

[15]. Tumours with high-risk progression scores were

classified mostly as class 2 (high risk), while tumours with

low-risk progression scores were classified mostly as class 1

(low risk) or class 3 (intermediate risk) (

p

= 3.2 10

22

[10_TD$DIFF]

,

x

2

test; Supplementary Table 2).

3.2.

12-gene progression score performance (all tumours

analysed)

The risk of progression may change during the disease

course, and recurrent and multifocal tumours may have

different biological properties. To mimic a potential clinical

use of the test, we classified patients using the highest score

obtained in the disease course for cases for which multiple

tumours were analysed (71 patients; 37 synchronous and

60 metachronous tumours in addition to the first tumour).

Using this approach, the progression score changed from

low risk to high risk (cut-off

optimal

) for 14 patients and

remained stable in 80% (57/71) of patients. The impact on

test performance using progression scores from all tumours

analysed is shown in Supplementary Table 3 and Supple-

mentary Table 4. An overview of assay performance using

the first tumour only and inclusion of later tumours is

shown in Supplementary Table 5. To address the impact of

analysing multiple tumours further, we performed a

multivariable time-dependent Cox regression analysis

including the maximum observed continuous EORTC risk

and progression score variables. We obtained a progression

score (continuous) hazard ratio (HR) of 1.81 (95% confi-

dence interval [CI] 1.32–2.48;

p

<

0.001) and an EORTC risk

(continuous) HR of 1.14 (95% CI 1.06–1.22;

p

[10_TD$DIFF]

<

0.001),

which are highly similar to the values presented in

Supplementary Table 4. Consequently, inclusion of all

tumours analysed did not have any large effect on the

overall test performance, partly because of the limited

number of patients included for whom multiple tumours

were analysed.

3.3.

Comparison of progression scores from paired FF and FFPE

tissues

To determine whether our findings using FF tumour tissue

might be translated to the standard clinical setting using

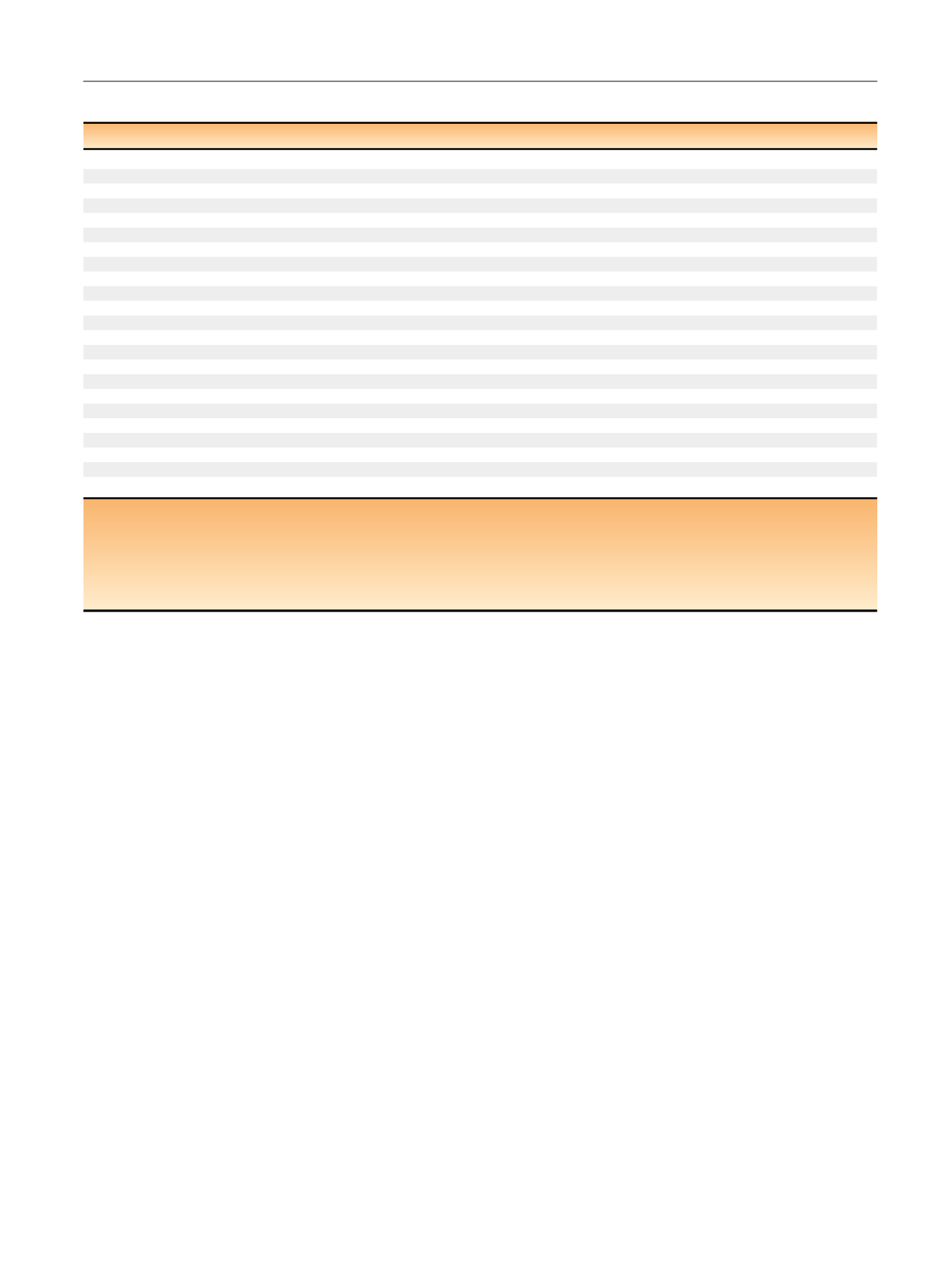

Table 2 – Cox regression analysis of progression-free survival with the first tumour in the disease course as the baseline

a[3_TD$DIFF]

HR (95% CI)

x

2

(df)

p

value

PA (%)

Univariate analysis (n = 578, 37 events)

Age

1.03 (1.00–1.06)

3.92 (1)

0.040

58.4

Gender (female vs male)

0.93 (0.43–2.05)

0.03 (1)

0.878

49.5

Stage (T1 + Cis vs Ta)

7.42 (3.67–15.04)

34.87 (1)

<0.001

75.5

Grade (high vs low + PUNLMP)

4.94 (2.32–10.51)

20.58 (1)

<0.001

70.1

Bacillus Calmette-Gue´rin (yes vs no)

0.63 (0.24–1.61)

1.07 (1)

0.329

53.8

Size ( 3 cm vs

<

3 cm)

1.40 (0.63–3.11)

0.63 (1)

0.415

53.2

Growth pattern (solid + mixed vs papillary)

4.45 (1.72–11.51)

6.70 (1)

0.002

55.5

Primary (yes vs no)

1.01 (0.53–1.93)

<

0.001 (1)

0.978

49.8

Multiplicity (multiple vs solitary)

1.48 (0.76–2.88)

1.29 (1)

0.248

53.0

Concomitant CIS (yes vs no)

3.59 (1.58–8.18)

7.03 (1)

0.002

56.5

EORTC risk score (

>

6 vs 6)

7.17 (3.28–15.71)

31.20 (1)

<0.001

73.3

EORTC risk score (continuous)

1.21 (1.14–1.28)

35.88 (1)

<0.001

78.4

Progression score (high vs low risk)

5.08 (2.23–11.57)

19.56 (1)

<0.001

68.1

[4_TD$DIFF]

Progression score (continuous)

2.39 (1.82–3.16)

41.85 (1)

<0.001

78.6

PA model (clinical)

81.8

PA model (clinical +

[4_TD$DIFF]

Progression score [continuous])

85.7

Multivariable model 1 (n = 517, 34 events)

55.84 (2)

<0.001

85.7

[4_TD$DIFF]

Progression score (continuous)

1.95 (1.44–2.65)

<0.001

Stage (T1 + CIS vs Ta)

4.21 (1.89–9.39)

<0.001

Multivariable model 2 (n = 578, 37 events)

53.36 (2)

<0.001

82.2

[4_TD$DIFF]

Progression score (continuous)

1.90 (1.39–2.58)

<0.001

EORTC risk (continuous)

1.13 (1.05–1.21)

0.001

HR = hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval; df = degrees of freedom; CIS = carcinoma in situ (concomitant); PA = prediction accuracy (Harrell’s concordance

index)

[1_TD$DIFF]

; PUNLMP = papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential; EORTC = European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer.

a

[5_TD$DIFF]

For patients with

[6_TD$DIFF]

non progression

[2_TD$DIFF]

>

[7_TD$DIFF]

12 mo of follow-up were

[8_TD$DIFF]

required to be included in the analysis. The clinical PA model included age, stage, grade, growth

pattern, and CIS. Bold indicates

p

<

0.05. The HR for continuous

[4_TD$DIFF]

progression score and EORTC scores is for a 1-unit increase. Multivariable Cox regression model

1 shows model variables (

p

<

0.1) after backward selection from a model starting with all significant (

p

<

0.05) variables from univariate Cox regression analysis

(ie, age, stage, grade, growth pattern, and concomitant CIS). Multivariable Cox regression model 2 included the

[4_TD$DIFF]

progression score and EORTC risk score only. All

variables were measured at the time of transurethral resection of the bladder.

E U R O P E A N U R O L O G Y 7 2 ( 2 0 1 7 ) 4 6 1 – 4 6 9

465