and amplification of

PPARG

,

GATA3, ERBB2

, and

E2F3/SOX4

( Fig. 4 ).

4.

Conclusions

Molecular subtypes of bladder cancer are enriched with

specific genetic alterations. As recognized previously

[[57_TD$DIFF]

68],

basal/SCC-like MIBCs frequently contain

RB1

mutations, a

property that they share with basal-like breast cancers

[[72_TD$DIFF]

79,80]. Basal/SCC-like MIBCs are also enriched with

NFE2L2

mutations, which have also been identified in lung and head

and neck squamous cancers

[[18_TD$DIFF]

21,22]. Luminal tumors

contain more alterations in

FGFR3

and

KDM6A

(also known

as

UTX

) genes that are more commonly mutated in NMIBCs

as compared with that in MIBCs

[1]. These observations

support the emerging conclusion that

FGFR3

mutations

mark the luminal MIBCs that correspond to the papillary

NMIBCs that have progressed to become muscle invasive.

Alterations affecting several transcription factors that

appear to play important roles in urothelial terminal

differentiation

[[73_TD$DIFF]

81,82](PPARG

,

GATA3

,

RXRA

, and

ELF3)

were also enriched in luminal cancers. Biological effects of

these alterations will need to be explored in future

functional studies.

The Lund subclassifications divide the UNC/MD Ander-

son/TCGA basal/SCC-like and luminal subtypes in ways that

have important biological and clinical implications. Al-

though they cluster together with the squamous/basal

tumors in the UNC, MD Anderson, and TCGA classifications,

the genetic alterations in the uroB tumors more closely

resemble those present in the luminal uroA subtype,

supporting the conclusion that they represent progressed

versions of the uroA cancers. The precise mechanisms that

cause them to appear more ‘‘basal’’ (at the molecular level,

and also in terms of their enrichment with squamous

histological features and lethality) will be very interesting;

their relatively high content of

RB1

and

NFE2L2

mutations

suggests possible mechanisms. The existence of uroB

tumors also suggests that basal versus luminal subtype

class ‘‘switching’’ is possible. Clinically, it will be interesting

to determine whether the uroA and uroB tumors are equally

sensitive to FGFR inhibitors.

[(Fig._4)TD$FIG]

ERCC2

NFE2L2

RB1

TP53

0

20

40

60

80

Basal

% of samples

SCCL

UroB Infil

GU

UroA

*

*

*

*

ELF3

ERBB2

ERBB3

FGFR3

FOXA1

GATA3

KDM6A

PIK3CA

RXRA

STAG2

0

10

20

30

40

Luminal

% of samples

SCCL

UroB

Infil

GU

UroA

*

*

EGFR

ERCC2

RB1_DEL

TP53_DEL

0

5

10

15

20

25

Basal

% of samples

SCCL

UroB Infil

GU

UroA

*

CDKN2A_DEL

E2F3

ERBB2

ERBB3

FGFR3

GATA3

PPARG

SOX4

0

20

40

60

80

Luminal

% of samples

SCCL

UroB Infil

GU

UroA

*

*

*

*

*

Mutation (Lund)

CNA (Lund)

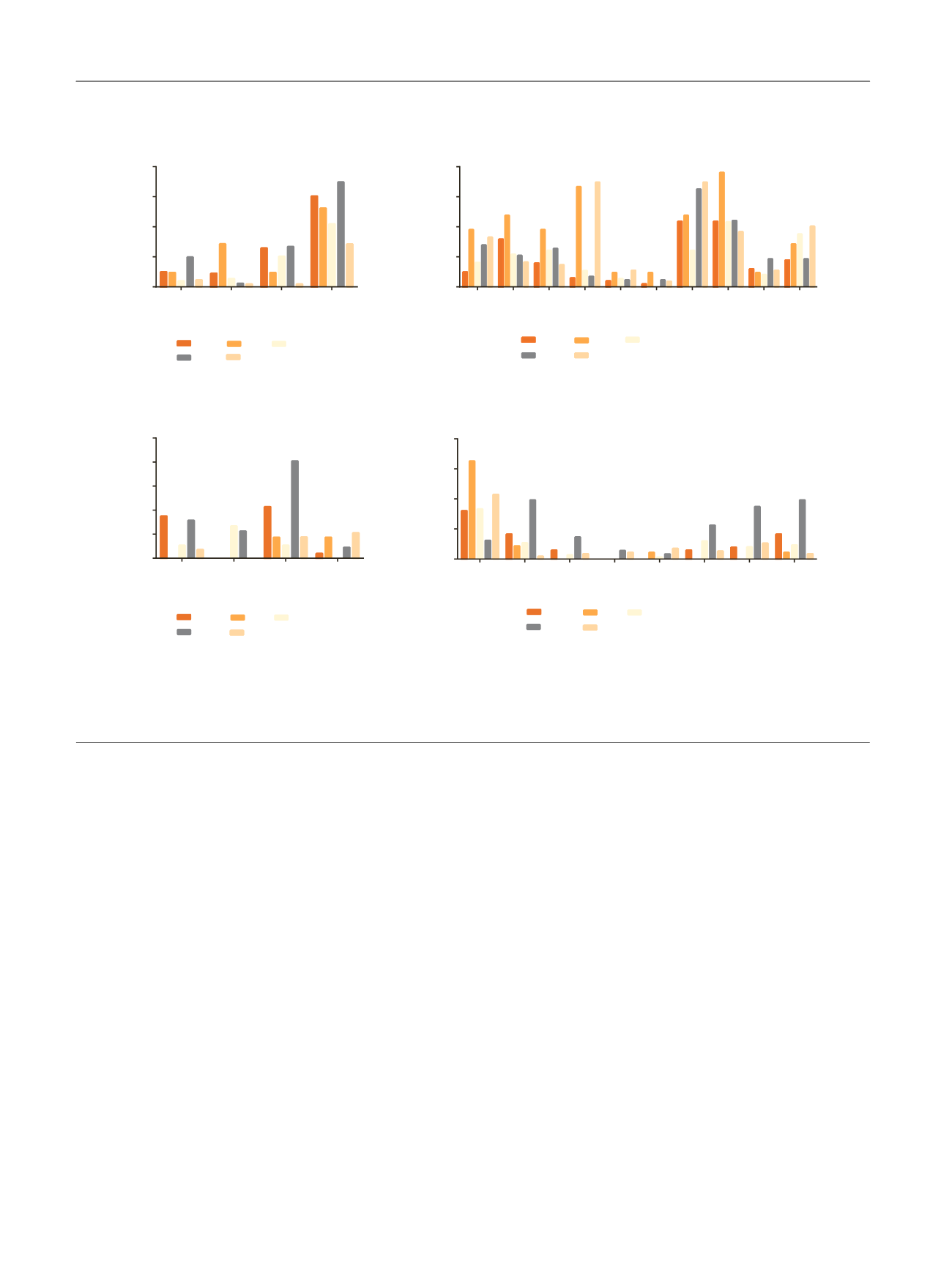

Fig. 4 – Enrichment of significantly mutated genes and CNAs in the Lund subtypes. Alterations are grouped according to predicted enrichment in basal

versus luminal tumors, and the results are displayed as percentages of tumors in each subtype that contained the indicated alteration. The CNAs

correspond to chromosomal amplification unless specifically identified as deletions (‘‘del’’). Fisher’s exact test was used to determine differences

between subtypes. CNA = copy number aberration; GU = genomically unstable; Infil = infiltrated; SCCL = squamous cell carcinoma like; uroA = urobasal

A; uroB = urobasal B. *

p

< 0.05 was considered significant.

E U R O P E A N U R O L O G Y 7 2 ( 2 0 1 7 ) 3 5 4 – 3 6 5

362