absolute difference in prostate-cancer mortality between

radically treated and nonradically treated matched groups,

which translated to circa three-fold higher hazard for the

latter cohort (no differences in other-cause mortality were

seen).

Treating the primary lesion in disseminated disease is

the gold standard in several cancer types such as ovarian

and renal cell

[4–6,13] .Median survival from peritoneal

carcinomatosis from gastrointestinal cancer has increased

from 6 mo to

>

2 yr with cytoreductive surgery plus

intraperitoneal chemotherapy

[14]. A SEER-Medicare study

of 9011 metastatic colon cancer patients showed that 2-yr

survival increases from 8% in the chemotherapy-only group

to 30% in the chemotherapy-plus–removal of the primary

tumor group

[15].

There also exist data in prostate cancer; disseminated

tumor cells in men with localized prostate cancer before

radical prostatectomy confer a five-fold increased risk of

subsequent metastases, but when detected after surgery

there is no increased risk, suggesting that an intact primary

lesion promotes clinical metastases

[16–18] .A subgroup

analysis from SWOG-8894 of 1286 men with metastatic

prostate cancer showed a 23% reduction in mortality in

those who had undergone prior radical prostatectomy

compared with those who had not

[19]. Retrospective case

series on men with likely occult metastatic disease (PSA

>

50 or N + disease) have demonstrated a survival advan-

tage for surgery of the primary tumor compared with

systemic therapy alone

[2,20,21]. A recent SEER report of

mortality outcomes in men with metastatic prostate cancer

and treated with radical therapy demonstrated 5-yr overall

survival and disease-specific survival advantage for patients

who underwent surgery or brachytherapy compared with

the nonradically treated group

[7] .However, the study had a

short median follow-up (16 mo), no data on many

important predictors, small numbers in the surgery

(

n

= 245) and brachytherapy (

n

= 129) arms, no external

beam radiation group, and significant patient–tumor

differences between groups at baseline, and it was not a

true population-based study. Data from the Munich Cancer

Registry of metastatic prostate cancer showed 55% 5-yr

overall survival in the surgical group versus 21% in the

nonsurgical group

[22]; again, these data are limited: small

numbers in the surgical arm (

n

= 74) compared with the

nonsurgical arms (

n

= 1464), heterogeneity of nonsurgical

treatments, and no attempt to adjust for patient–tumor

differences between the groups.

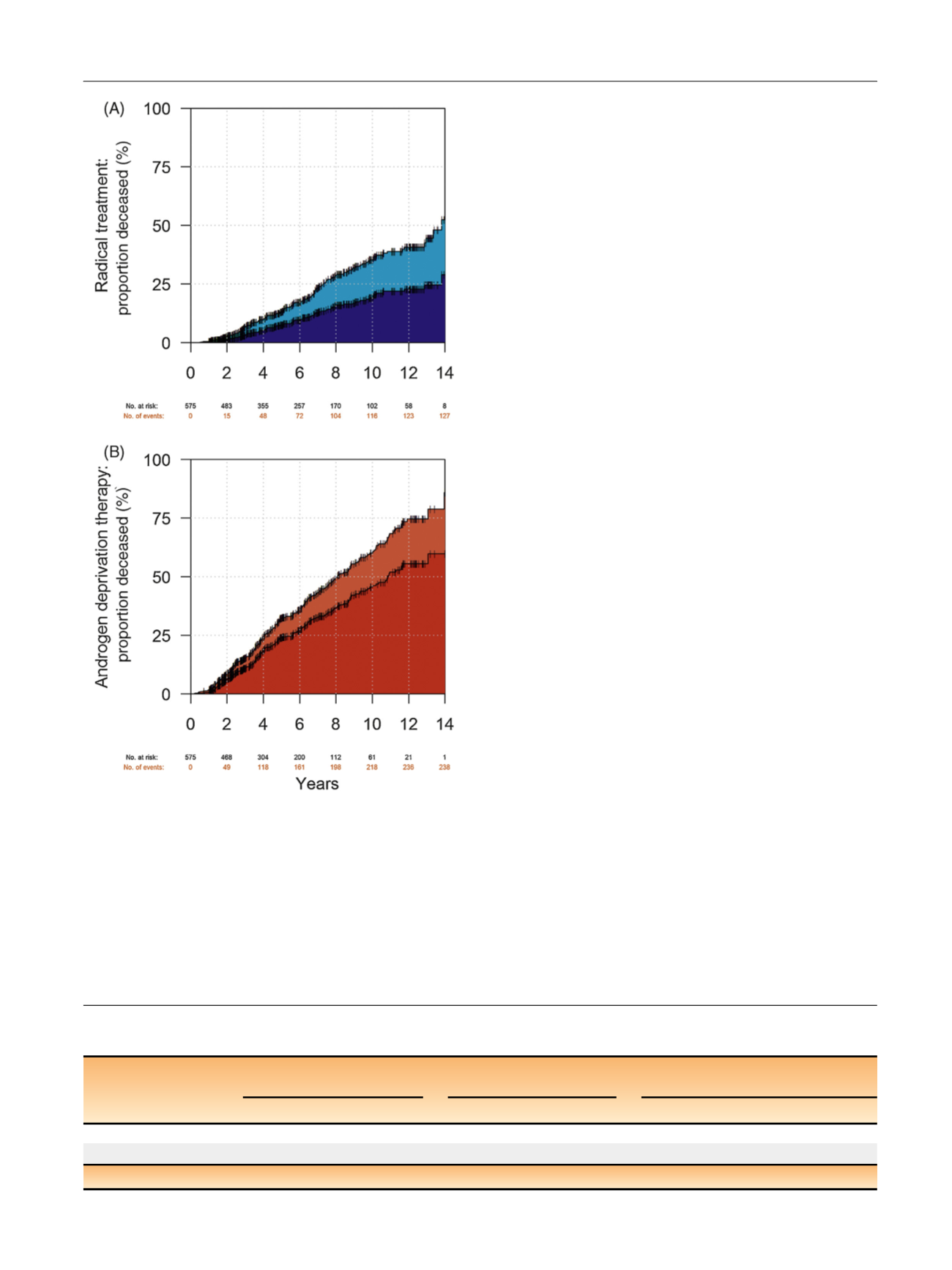

[(Fig._2)TD$FIG]

Fig. 2 – Cumulative incidence curves of prostate-cancer and other-cause

mortality for the cohort of (A) radically treated and (B) androgen

deprivation patients with PSA > 50 frequency matched by PSA, clinical

stage, M stage, tumor grade, Charlson comorbidity index, age, and year

of diagnosis (

n

= 1150). White = alive; light blue = other-cause mortality

in the radical therapy group; dark blue = prostate-cancer mortality in

the radical therapy group; light red = other-cause mortality in the

androgen deprivation group; and dark red = prostate-cancer mortality

in the androgen deprivation group. PSA = prostate-specific antigen.

Table 3 – Mortality figures and crude and multivariable model–adjusted subdistribution hazard ratios for androgen deprivation versus

radical therapy for prostate-cancer and other-cause mortality for the subgroup of frequency-matched PSA > 100 cases (

n

= 176)

No. of deaths

Crude sHR (95% CI)

p

value Multivariable model–adjusted

sHR (95% CI)

p

value

ADT

Radical treatment

ADT vs radical treatment

ADT vs radical treatment

Prostate-cancer mortality 38/88 (43%)

19/88 (22%)

2.66 (1.54–4.59)

<

0.001

2.93 (1.57–4.02)

<

0.001

Other-cause mortality

4/88 (4.5%)

8/88 (9.1%)

0.51 (0.15–1.67)

0.3

0.45 (0.12–1.17)

0.1

ADT = androgen deprivation therapy; CI = confidence interval; sHR = subdistribution hazard ratio.

E U R O P E A N U R O L O G Y 7 2 ( 2 0 1 7 ) 3 4 5 – 3 5 1

349